On paper, owning Bitcoin or Ethereum in Bangladesh isn’t illegal. But if you try to trade it, mine it, or even hold it in a wallet, you could end up in jail. That’s the reality in Bangladesh as of 2026 - a country where cryptocurrency isn’t explicitly banned by law, but every move you make with it could trigger a criminal investigation.

How Bangladesh’s Crypto Ban Works Without a Law

Bangladesh doesn’t have a single law that says, "Crypto is illegal." Instead, it uses existing financial rules to crush crypto activity. The Bangladesh Bank is the central bank of Bangladesh, established in 1972, responsible for monetary policy and financial system oversight has been issuing warnings since 2014. By 2017, it declared cryptocurrency transactions illegal under the Foreign Exchange Regulations Act of 1947 and the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2012. These laws were never written for Bitcoin - but now they’re the main tools used to arrest people.

The Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) monitors suspicious transactions. If someone sends money to a TRC20 wallet or uses a crypto exchange like Binance to buy Bitcoin, the FIU flags it. The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) then steps in. In 2024, at least 17 people were arrested in Dhaka for running hidden crypto mining rigs. Authorities didn’t charge them with "owning crypto." They charged them with violating anti-money laundering laws and foreign exchange rules.

Why Mining Is a Direct Crime

Crypto mining is treated as a serious offense. It’s not just about using electricity - it’s about bypassing the entire financial system. Mining requires hardware, power, and internet. In Bangladesh, where power grids are unreliable and electricity is subsidized, running mining rigs is seen as stealing public resources and enabling illegal capital flight.

The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act is also used here. Section 57 of this law criminalizes digital activities that "harm national security or public order." Authorities have used it to justify shutting down mining farms, seizing computers, and arresting operators. One miner in Chittagong was sentenced to two years in 2023 after police found 42 ASIC miners in his garage. He wasn’t charged with crypto - he was charged with "illegal financial activity under the ICT Act."

What Happens When You Get Caught

There’s no fine. No warning. No license to apply for. If you’re caught trading or mining crypto, you’re arrested. The charges are usually under:

- Foreign Exchange Regulations Act of 1947 (unauthorized cross-border transfers)

- Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2012 (structuring transactions to hide origin)

- ICT Act Section 57 (digital crime against state interests)

Penalties can include jail time from 6 months to 7 years. There’s no bail process for crypto-related arrests - the court treats them as high-risk financial crimes. In 2024, a Dhaka-based trader who sent $120,000 in Bitcoin to a Malaysian exchange was sentenced to 4 years. His defense? "I didn’t know it was illegal." The judge didn’t accept it.

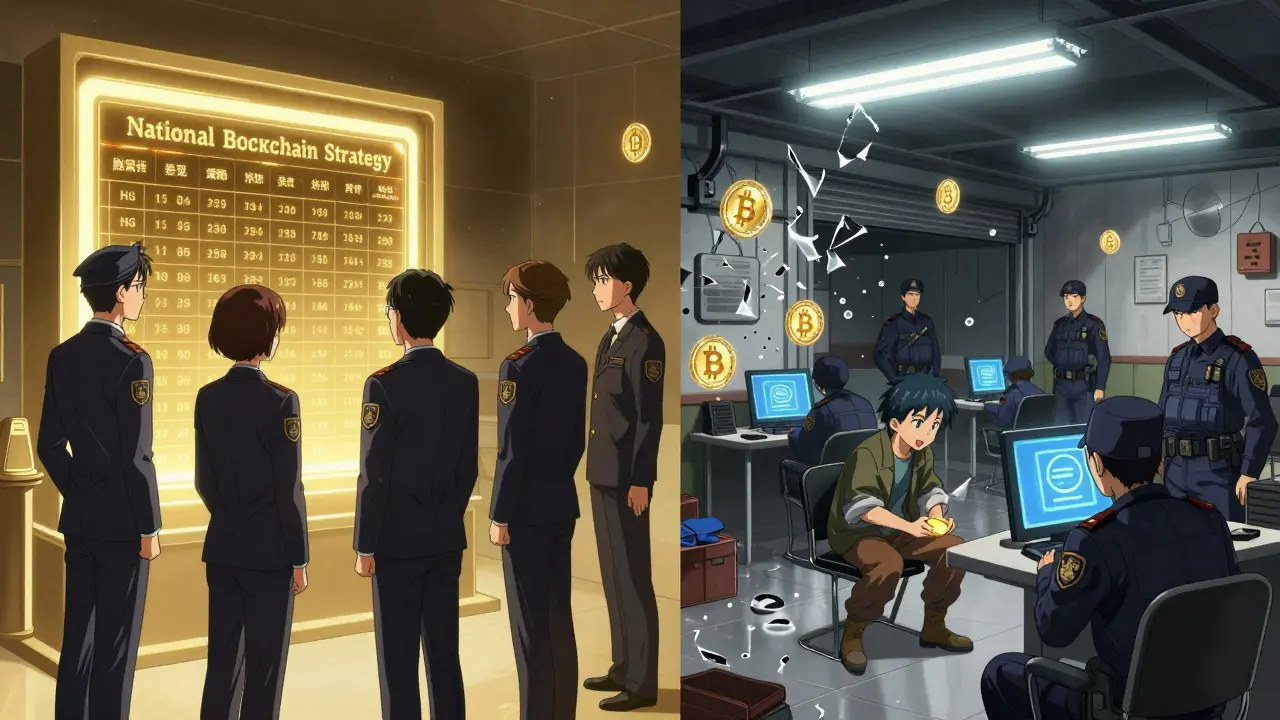

Blockchain Is Fine - Just Not Crypto

Here’s the contradiction: Bangladesh’s government loves blockchain - but hates cryptocurrency.

In 2020, the Bangladesh Computer Council launched the National Blockchain Strategy. It’s designed to digitize land records, voter IDs, and tax systems using blockchain. The government even partnered with foreign tech firms to build public blockchain networks.

But if you try to use that same technology to send money to a friend or buy Bitcoin? That’s a crime. The disconnect is glaring. One part of the government is building secure digital ledgers for public services. Another part is arresting people for using the same tech to move money privately.

Why People Still Use Crypto Anyway

Despite the risks, crypto use hasn’t disappeared. It’s gone underground.

People use peer-to-peer platforms like LocalBitcoins and Paxful. They trade in cash through trusted networks. Some use Telegram groups to match buyers and sellers. Others convert crypto to stablecoins like USDT, then send them via TRC20 wallets - which are nearly impossible to trace without access to blockchain analytics tools Bangladesh doesn’t have.

Remittance workers abroad are a big driver. Many Bangladeshis working in the Middle East send money home through crypto because traditional channels like Western Union charge 10% and take days. Crypto can be faster and cheaper - even if it’s risky. One 2023 survey by a Dhaka-based research group found that 1 in 12 urban adults had used crypto in the past year, mostly for remittances.

How Bangladesh Compares to Its Neighbors

Bangladesh is an outlier in South Asia.

Pakistan, just next door, created the Pakistan Digital Assets Authority (PDAA) in May 2025. It licenses exchanges, allocates 2,000 megawatts of power for mining, and even created a National Crypto Committee. Pakistan’s informal crypto market hit $25 billion in 2023.

India allows crypto trading with taxes. Sri Lanka lifted its ban in 2023. Nepal still restricts it - but doesn’t arrest people. Bangladesh is the only country in the region that treats crypto ownership as a potential criminal act.

This isolation is starting to hurt. Foreign investors avoid Bangladesh. Local startups can’t build DeFi tools. Even fintech firms that work with mobile money - like bKash and Nagad - won’t touch crypto-related projects for fear of legal exposure.

International Pressure Is Building

Bangladesh is not compliant with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) standards. FATF Recommendation 15 requires countries to regulate virtual asset service providers. Bangladesh doesn’t even recognize them as a category.

The FATF has flagged Bangladesh for "high risk" in its 2025 global report. That means banks in the EU and U.S. now treat Bangladeshi financial institutions as high-risk. It makes international transfers harder, increases compliance costs, and pushes more people toward crypto just to get money out.

There’s growing pressure from the IMF and World Bank to reform. But so far, the Ministry of Finance has shown no interest in changing course. The official line remains: "Crypto threatens financial stability. We must protect the public."

What About Taxes?

No one knows.

The National Board of Revenue (NBR) says it applies the Income Tax Ordinance of 1984 to crypto profits. But there are no forms, no guidelines, no reporting system. If you make $10,000 trading Bitcoin, you’re supposed to declare it. But how? Where? The NBR doesn’t have a crypto tax form. So people don’t report. And the government doesn’t audit.

This creates a gray zone: crypto is illegal to trade, but you’re technically supposed to pay tax on profits. It’s a trap. Report it, and you admit to a crime. Don’t report it, and you risk tax fraud charges.

Who’s Really at Risk?

It’s not the wealthy. They have lawyers and offshore accounts.

It’s the young tech workers, the remittance senders, the small traders, the students learning blockchain. The people who don’t have access to legal advice or political connections. The ones who see crypto as a way out of a broken financial system.

One 23-year-old student in Sylhet was arrested in 2024 for buying $300 worth of Ethereum to pay for an online course. He didn’t sell it. He didn’t mine. He just bought it. He spent three months in jail before the case was dropped - but his laptop was seized, and his university suspended him.

The Future: Will Bangladesh Change?

Right now, the government shows no sign of softening. The Bangladesh Bank still issues quarterly warnings. The FIU still monitors wallet addresses. The CID still raids homes.

But global trends won’t stop. More people will use crypto. More remittances will flow through it. More startups will try to build on it. And as neighboring countries like Pakistan move toward regulation, Bangladesh’s isolation will become an economic liability.

Either the government will update its laws - or it will keep arresting people who are just trying to use technology that the rest of the world has already accepted.

For now, the message is clear: In Bangladesh, crypto isn’t just risky. It’s dangerous.

Athena Mantle

January 20, 2026 AT 23:09Okay but like… why is everyone acting shocked? 🤦♀️ The state has always weaponized vague laws to control people. It’s not about crypto-it’s about control. Bangladesh’s elite don’t want anyone bypassing their financial chokehold. Blockchain? Sure, use it for land records. But let a kid buy ETH to pay for a course? Jail time. Classic.

Also, the fact that they’re using Section 57 of the ICT Act to arrest people for *owning* crypto? That’s not law. That’s theater. They’re not enforcing rules-they’re enforcing fear. And it’s working. People are scared. But guess what? Scared people don’t innovate. They just hide.

Meanwhile, the government’s building blockchain for public services while criminalizing the same tech for private use. It’s like giving someone a key to your house… but throwing them in jail if they use it to open their own front door. 🤡

And don’t even get me started on the tax gray zone. Pay taxes? You admit guilt. Don’t pay? You’re a tax evader. It’s a trap designed to keep people powerless. This isn’t policy. It’s psychological warfare.

And yet… people still use it. Because when your system is broken, you don’t wait for permission to fix it. You just do it. Quietly. Carefully. And that’s why this will never truly work. You can’t outlaw innovation. You can only delay it.

Also, 1 in 12 urban adults using crypto? That’s not a fringe movement. That’s a revolution happening under the radar. And the government? They’re still writing warnings like it’s 2014. 😴

Meanwhile, Pakistan’s giving out megawatts for mining. India’s taxing it. Sri Lanka lifted the ban. Bangladesh? Still arresting students. The future is here. It’s just not evenly distributed. 🌍✨

carol johnson

January 22, 2026 AT 11:38OMG I CRIED reading this. 😭 Like… who even *is* this government?? They’re literally punishing people for using tech that’s already everywhere else. It’s not just cruel-it’s *embarrassing*. 🤦♀️

And the fact that they’re using the ICT Act?? That’s like charging someone with treason for using Wi-Fi. I’m so done.

Melissa Contreras López

January 23, 2026 AT 14:33This is one of those moments where you realize how deeply human resilience can be. People aren’t using crypto because they’re tech bros or criminals-they’re using it because they’re parents sending money home, students paying for courses, workers trying to survive a broken system.

The government’s fear isn’t about money laundering. It’s about losing control. And that’s a fear that always backfires.

There’s beauty in how quietly people are building alternatives-Telegram groups, cash trades, TRC20 wallets. No fanfare. No hashtags. Just survival. And that’s the most powerful kind of resistance.

It’s not about whether crypto is good or bad. It’s about whether people deserve to have tools that give them freedom. And honestly? The answer is obvious.

Keep going, Bangladesh. The world’s watching. And we’re rooting for you.

Mike Stay

January 24, 2026 AT 18:12It is of paramount importance to recognize that the regulatory posture adopted by the Central Bank of Bangladesh is not merely a matter of financial policy, but rather a reflection of a broader institutional anxiety concerning sovereignty, monetary autonomy, and the preservation of formal financial architecture in the face of decentralized technological disruption.

While the absence of an explicit statutory prohibition against cryptocurrency may appear, on a cursory examination, to constitute a legal lacuna, the invocation of the Foreign Exchange Regulations Act of 1947 and the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2012 demonstrates a sophisticated, albeit draconian, form of legal adaptation-commonly referred to in jurisprudential circles as 'regulatory creep'.

Moreover, the utilization of Section 57 of the ICT Act to criminalize private digital financial activity represents a troubling conflation of national security concerns with economic governance, a practice historically observed in states undergoing authoritarian consolidation.

The paradox of state-sponsored blockchain infrastructure coexisting with the criminalization of peer-to-peer cryptocurrency usage is not merely ironic-it is structurally unsustainable. One cannot simultaneously invest in distributed ledger technology for public service digitization while outlawing its most fundamental application: decentralized value transfer.

Furthermore, the international implications are profound. The FATF’s 'high risk' designation, coupled with the reluctance of global financial institutions to engage with Bangladeshi entities, constitutes a form of economic isolationism that will inevitably impede foreign direct investment, technological collaboration, and financial inclusion.

It is not hyperbole to suggest that Bangladesh stands at a crossroads: one path leads to regulatory modernization, alignment with global standards, and economic integration; the other leads to deeper repression, brain drain, and technological irrelevance.

The youth of Bangladesh are not criminals. They are early adopters. And history has shown that states which criminalize innovation do not preserve stability-they preserve obsolescence.

Arielle Hernandez

January 25, 2026 AT 11:47Let’s clarify a critical misconception: Bangladesh has not banned cryptocurrency. It has banned *unregulated financial intermediation*. The distinction matters. The central bank doesn’t object to blockchain-it objects to unmonitored capital flows. The real issue is the absence of a regulatory framework, not the technology itself.

Section 57 of the ICT Act was never intended for crypto enforcement. Its application here is a clear case of legal overreach. Courts have repeatedly ruled that laws must be applied as written, not stretched to fit political agendas. This is not legal enforcement-it’s legal fiction.

The tax gray zone is equally problematic. If the NBR claims crypto profits are taxable under the Income Tax Ordinance of 1984, then it must provide reporting mechanisms. It hasn’t. That’s not a loophole-it’s administrative failure.

Comparing Bangladesh to Pakistan is misleading. Pakistan created a regulatory sandbox. Bangladesh has created a surveillance trap. The difference is intentionality: one seeks to integrate, the other to suppress.

And yes-remittance workers are the real story here. When traditional channels charge 10% and take 3 days, crypto at 1% and 10 minutes isn’t rebellion. It’s rationality. Criminalizing rationality doesn’t protect the system-it breaks it.

Until Bangladesh establishes a clear, transparent, and enforceable regulatory regime, arrests will continue. But so will crypto use. Because people don’t stop solving problems just because the government says they can’t.

HARSHA NAVALKAR

January 26, 2026 AT 06:28They should just let it be. Why punish people for trying to survive? It’s not like they’re robbing banks. Just… let them be. I don’t even know why I’m writing this. No one cares.

Shamari Harrison

January 27, 2026 AT 22:16This is a textbook case of institutional cognitive dissonance. The government is investing in blockchain for land records and voter IDs-technology that requires public trust, transparency, and accessibility. But when citizens try to use the same tech to send money to family abroad? Suddenly it’s a crime.

There’s no technical reason for this contradiction. It’s purely political. The state fears losing control over financial flows. But controlling money doesn’t mean controlling people. And the more they try to suppress it, the more it spreads.

What’s happening here isn’t unique. We’ve seen it before-in prohibition, in censorship, in the war on drugs. Criminalizing behavior that’s already widespread doesn’t eliminate it. It just makes it more dangerous.

The real victims aren’t miners or traders. They’re the students, the workers, the mothers sending money home. They’re not trying to break the system. They’re trying to make it work.

And if the government doesn’t change course, the only thing it’ll be remembered for isn’t its blockchain initiative. It’ll be the arrests.

Nadia Silva

January 29, 2026 AT 18:01Typical third-world chaos. You can’t have a functioning economy if people are running around using unregulated digital cash. This is why Bangladesh is stuck. They need discipline, not tech fantasies. Crypto is a Western scam. Let them have their Bitcoin. We’ll stick to real money.

tim ang

January 30, 2026 AT 03:27Bro… I just read this and I’m shook. 😳 Like… imagine getting arrested for buying $300 of ETH to pay for a course? That’s wild. I feel bad for these people. They’re just trying to learn and help their families. The system’s broken. Not them.

Also, why is no one talking about how the government is using blockchain for public stuff but criminalizing it for private use?? That’s like… the ultimate hypocrisy. 😤

Julene Soria Marqués

January 31, 2026 AT 14:27Okay but let’s be real-this is just another authoritarian regime flexing. They don’t care about money laundering. They care about control. And if you’re smart enough to use crypto? You’re a threat.

Also, the fact that they’re using Section 57? That’s the same law they use to jail journalists. So… crypto users are now ‘threats to national security’? Cool. I’m sure the next thing is banning VPNs.

And the tax thing? Classic. Pay taxes = admit guilt. Don’t pay taxes = tax fraud. It’s a no-win. They don’t want you to win. They just want you to shut up.

MOHAN KUMAR

February 1, 2026 AT 09:24People in Bangladesh are not criminals. They are just trying to survive. Why punish them? The government should fix the system, not arrest people.

Andy Marsland

February 3, 2026 AT 08:27Let me be perfectly clear: this isn’t about crypto. This is about the collapse of the rule of law in Bangladesh. When a state begins using outdated, unrelated statutes to criminalize new technologies, it’s not enforcing order-it’s revealing its own illegitimacy.

The Foreign Exchange Regulations Act of 1947 was written when the world was on the gold standard. The Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2012 was designed for cash smuggling, not TRC20 wallets. To apply these laws to Bitcoin is not legal interpretation-it’s legal absurdity.

And the ICT Act? Section 57 was meant to combat cyberbullying and fake news. Now it’s being used to jail students? This is not justice. This is persecution dressed in legal robes.

The government’s hypocrisy is staggering. They spend millions on blockchain for land records-technology that relies on the same cryptographic principles as Bitcoin-and then arrest citizens for using that same tech to send money home. This isn’t policy. It’s cognitive dissonance on a national scale.

And the tax issue? The NBR claims crypto profits are taxable, but provides no forms, no guidance, no system. That’s not a tax policy-it’s a trap. They want you to break the law so they can punish you. That’s not governance. That’s entrapment.

Meanwhile, Pakistan is creating a national crypto authority. India is taxing it. Sri Lanka lifted its ban. Nepal doesn’t arrest people. And Bangladesh? They’re arresting 23-year-olds for buying Ethereum.

This isn’t about financial stability. It’s about power. And power that fears innovation is power that’s already dying.

Anna Topping

February 4, 2026 AT 00:24It’s funny how the same people who say ‘technology is neutral’ suddenly get scared when it’s used by the wrong people. Crypto isn’t good or bad-it’s a tool. And right now, for millions in Bangladesh, it’s the only tool that works.

The government wants to control money. But money doesn’t care about borders. It never has. And it never will.

They’re building blockchain for land records. But if you try to use it to send $50 to your cousin? Jail. That’s not a policy. That’s a paradox with teeth.

And the worst part? They think they’re protecting the people. But they’re just protecting themselves.

katie gibson

February 5, 2026 AT 09:42so like… they’re literally arresting people for using crypto?? 😭 i’m crying. this is insane. i thought this was a joke. no one’s that dumb. but they are. they are so dumb. 🤦♀️

also… why is blockchain fine but crypto bad?? that’s like saying ‘you can use a knife to cut veggies but not to eat with’

also also… $300 for a course?? that’s it?? they arrested someone for that??

my brain hurts. 😵💫

Ashok Sharma

February 6, 2026 AT 02:13Respectfully, the government must protect the financial system. Cryptocurrency is unregulated and poses risks to national economic stability. While the hardship faced by individuals is understood, the broader consequences of unchecked digital currency must be prioritized.

It is better to enforce existing laws than to allow chaos to spread.

Margaret Roberts

February 7, 2026 AT 05:57Let’s be honest-this is all a distraction. The real story? The government is using crypto arrests to cover up corruption. Every time they jail someone for mining, they seize their equipment. Who gets that gear? Not the public. Not the state. Someone else.

And the blockchain projects? They’re just a front. The real tech is being sold to foreign contractors. Meanwhile, regular people get arrested for using the same tech to send money home.

It’s not about security. It’s about power. And it’s rigged.

Also… did you know the FIU’s ‘wallet monitoring’ system? It’s built by a company owned by a minister’s cousin. Coincidence? I think not.

They’re not fighting money laundering. They’re fighting transparency.

Matthew Kelly

February 7, 2026 AT 20:45Man… I just read this and I’m sitting here in Canada thinking… wow. People are risking jail just to send money home? That’s insane. But also… kind of beautiful? They’re not trying to break the system-they’re trying to make it work.

And the fact that the government’s building blockchain for public stuff but criminalizing private use? That’s like giving someone a key to the front door… but jailin’ them if they use it to let their kid in.

Hope things change for them. They deserve better.

Adam Fularz

February 8, 2026 AT 14:11Why are people even doing this? It’s obvious. If you want to use crypto, move to a country that allows it. Don’t risk your freedom for a digital asset. This isn’t a human rights issue-it’s a stupid choice.

Also, blockchain? That’s fine. But crypto? It’s a Ponzi scheme. Everyone knows it.

Brenda Platt

February 10, 2026 AT 03:59This is why I believe in people. Even when the system tries to crush them, they find a way. They’re not criminals. They’re connectors. They’re lifelines. They’re the quiet heroes keeping families together.

And the fact that the government is building blockchain for public good while punishing private use? That’s not policy. That’s a betrayal.

But here’s the thing-you can’t stop innovation. You can only delay it. And when you delay it with jail time? You don’t win. You just make the next generation even more determined.

Keep going. We see you. And we’re with you.

Barbara Rousseau-Osborn

February 10, 2026 AT 14:42These people are fools. Crypto is a scam. It’s not real money. It’s digital glitter. And now they’re going to jail? Good. Maybe now they’ll learn not to be so gullible.

Also, the fact that they’re using blockchain for land records? That’s fine. But crypto? No. Never. It’s a Western capitalist trap. Bangladesh should stay traditional.

And if you think this is harsh? Wait until you see what happens next. The crackdown is just beginning.

Athena Mantle

February 12, 2026 AT 09:37Replying to myself because I can’t stop thinking about this: the 23-year-old student arrested for buying $300 of ETH? He didn’t sell it. He didn’t mine it. He just bought it to pay for a course. That’s not a crime. That’s education.

And the judge didn’t accept ‘I didn’t know it was illegal’ as a defense? That’s not justice. That’s tyranny.

They’re not protecting the financial system. They’re protecting their own power.

And the worst part? The people who are getting arrested? They’re the ones who believe in the system. They’re trying to make it work. They just didn’t know the rules were rigged.

Shamari Harrison

February 13, 2026 AT 08:15Replying to Athena: You nailed it. The real tragedy isn’t the arrests. It’s the fact that these people had no warning. No guidance. No forms. No system. Just a law that didn’t exist on paper but was enforced with jail cells.

That’s not law. That’s a trap.

And the government knew it. They just didn’t care.